Part of supporting managers in addressing burnout is helping them understand what it looks like. Many see burnout as simply a synonym for ‘feeling tired,’ but the condition is multifaceted and must be understood in its entirety in order to be managed effectively.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), burnout is “a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” and is characterised by three dimensions:

1. Exhaustion

Exhaustion can take a number of forms, including physical, mental and emotional depletion.

Levels of exhaustion often correlate to the volume of an employee’s workload but can also be exacerbated by factors such as low job control, which can drain employees’ sense of involvement and engagement with their work.

We all know exhaustion, and many people think burnout stops here. But if you’re exhausted but love what you’re doing and are achieving goals, you’re not necessarily burned out. Rather, burnout is the combination of exhaustion with the other two dimensions.

2. Cynicism

Employees experiencing burnout often develop a cynical outlook, mentally distancing themselves from their work and their colleagues and approaching tasks with negativity or even callousness.

When you see people starting to hate their job, hate the people they work with and hate everything about their role, that’s a lot more problematic than the exhaustion piece when we’re trying to fix the situation. Once someone grows that cynicism, it’s a tough road to come back from.

3. Reduced professional efficacy

This dimension of burnout could involve increases in mistakes and feelings of incompetence, which are often not grounded in truth.

You might be very capable, but because of burnout, and because of the pressures that you’ve been put under or the culture you’re under, you’re starting to make mistakes and you’re starting to doubt your capabilities. Given that employees experiencing this symptom tend to take longer to complete tasks, it can create a vicious cycle of playing catch-up and lead to a “burnout spiral”.

Combating burnout through sustainable work practices

Managing the dimensions of burnout explained above requires transparency and open communication from leaders to ensure employees don’t begin to self-blame, which only exacerbates the issue.

Burnout is not the fault of the individual. It’s not something that they have or haven’t done that has called them to burnout. It’s not that they aren’t good at prioritising. It is chronic workplace stress, and so it’s the structure and culture within the organisation that’s creating this environment.

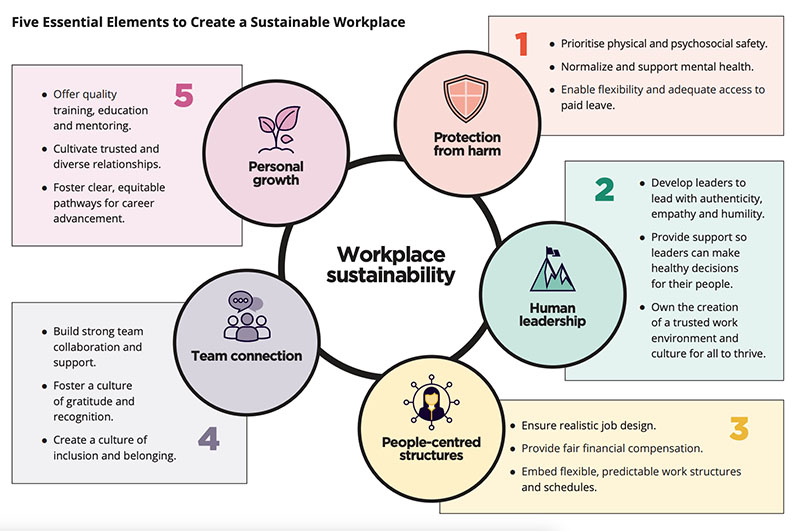

There is a five-part framework for creating a sustainable workplace – i.e., a workplace where burnout is less likely to occur.

The five foundations of a sustainable workplace include personal growth through training and career development, protection from harm and strong connections among teams.

See the full framework below:

Source: Infinite Potential

Source: Infinite Potential

One of the most important aspects of this sustainable workplace model is people-centred structures. This has so much to do with an employee’s wellbeing. Look at the way a job is structured or designed, and ask yourself, ‘Can one person actually do that job within the time allocated?’ ‘Are they getting paid enough that they can live and not worry about the rent?’ Thinking about all of these structural things will do much more for wellbeing than other initiatives.

While providing career development opportunities to employees whose workloads we are trying to reduce might seem counterintuitive, these opportunities are essential to give employees a sense of purpose and thus mitigate burnout.

They still want to grow. They want to do less work, but to keep growing professionally and as a person. So don’t think that if we want to improve people’s wellbeing, it’s all about just taking stuff away from them. Instead, it’s about providing opportunities for meaningful work and reducing the volume of stress-inducing tasks.

To effectively apply this structure, employers must be willing to test sustainable work strategies that work for them. No one knows the right answer. There is not going to be one right way [to approach] the future of work. It’s going to be different within organisations and within teams, and it’s going to change. So, be open to experimentation.

If you’re engaging with people on how you should try something, and telling them, ‘This is an experiment and it might not go well,’ people really buy into that. So don’t be afraid to try it.